Rendering Memories in Color and Line

Collection

Curator Renée Maurer on her new permanent collection selection on view in Gallery 116.

The new installation in Gallery 116 brings together a diverse range of representational and abstract art that uses scale, color, line, and texture to show the impact of political and psychological struggles. The artists featured—who are from different countries and time periods—tackle stories of hardship facing communities; some offer measures of hope. The central piece in the gallery, on view for the first time at the Phillips, is the powerful painting Refugee: Woman and Children (2000) by Hung Liu (1948-2021).

Liu’s early life in China was defined by Mao Zedong’s communist regime that subjected her to years in a labor camp as part of her proletarian reeducation. At the time, many educated people, out of fear of the past, burned photographs and family records. Liu recalled, “You couldn’t keep anything personal…that is why I am so interested in photographs…in subjecting the documentary authority of historical photographs to the more reflective process of painting.”

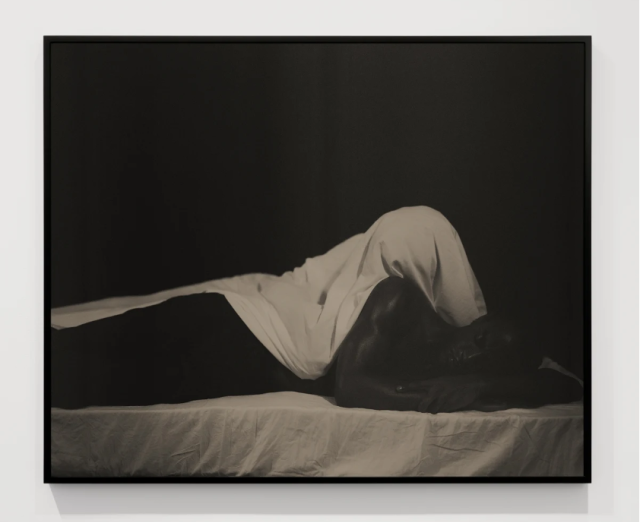

Having trained in mural painting and social realism in Beijing, Liu immigrated to the US in 1984. Seven years later, she went back to China and uncovered several hundred black-and-white photographs from before the revolution; these portraits of laborers, orphaned children, women, villagers, and soldiers became source material for her art upon her return to the US. For her process, Liu enlarged and painted the subject of her photograph, then added color, texture, and symbolic images to her canvas. She developed a style called “weeping realism” by dripping linseed oil over painted areas to create the impression of tears. Gravity pulled at the paint, unifying and dissolving the image, emphasizing the passage of time and the blurriness of memory. Refugee: Woman and Children references a photograph of a desperate mother trying to sell her infants. Each figure expresses anguish and fear. The background features a crane, other birds, a lotus blossom, and Buddha figures interpreted as blessings for the family on their arduous journey. Liu explained: “I hope to wash my subjects of their otherness and reveal them as dignified even mythic figures….My focus is really the human face, the human struggle, the epic journey. I am enshrining the anonymous working class who never had a voice.”

On display opposite Liu’s painting is Benny Andrew’s Trail of Tears (2005). Andrews uses cloth, paint, straw, and string to render the forced migration of the Eastern Woodlands Indians (including the Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Chocktaw, and Seminole tribes) from southeast America to west of the Mississippi River. By it, Ellington Robinson’s Never Forget on Ice (2013) explores how economics and culture are used to create mutable boundaries that define states and countries. Karel Appel’s La Grande Tete (Big Head) (1964) and Chaïm Soutine’s Return from School after the Storm (c. 1939) foreground anxieties from the Nazi occupation of Europe. Sylvia Snowden’s loaded brushwork conveys the physical and emotional struggles of her subject George Chavis (1983) whom she observed in her DC neighborhood. William Gropper’s Minorities (1938 or 1939) features a procession of figures braving harsh travel during war. Elias Sime’s Yediro Suk (1996) references the relocation of the Gurage ethnic group from southwestern Ethiopia to the capital Addis Ababa. Aimé Mpane addresses the aftermath of colonial and autocratic regimes in Congo with rough‐hewn painted portraits on wood of subjects from the streets of Kinshasa.

As you explore the gallery, consider the physicality of the works and the difficult journey that each one brings. What connects these artworks to each other? How do the artists use their various materials—paint, wood, photographs, fabric, etc—to express emotions? How do they connect with you and your life experiences?