Examining and Treating Villon’s Gallic Cock

Collection, Conservation Studio

Sculpture conservator Simona Cristanetti on her recent work treating Raymond Duchamp Villon’s Gallic Cock in the Phillips’s conservation studio.

Gallic Cock by Raymond Duchamp Villon was created in 1916 while the artist convalesced in a French hospital. It was conceived as an ornament for a portable theater and is made of plaster set within a painted black wood oval frame. The relief depicts a gilded rooster standing with one foot on the painted red rising sun, while the sun’s rays burst onto the black sky in the background. Three cast bronze versions of this work also exist; one of them is in the collection of the Hirshhorn Museum across town.

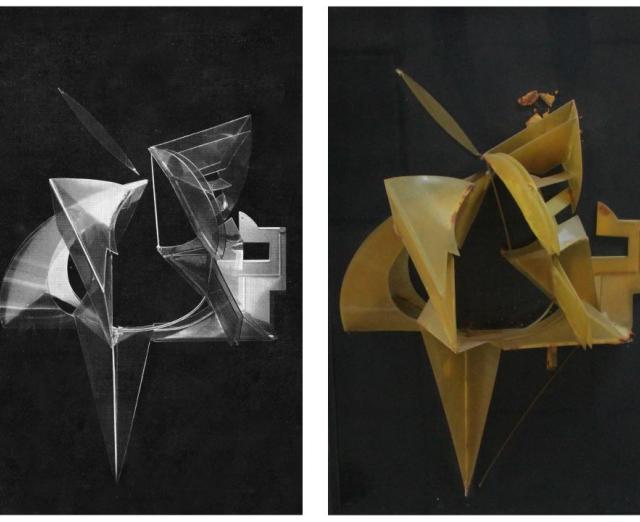

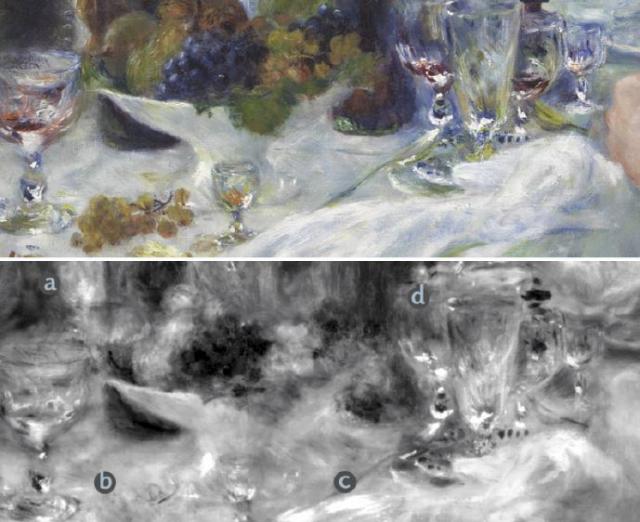

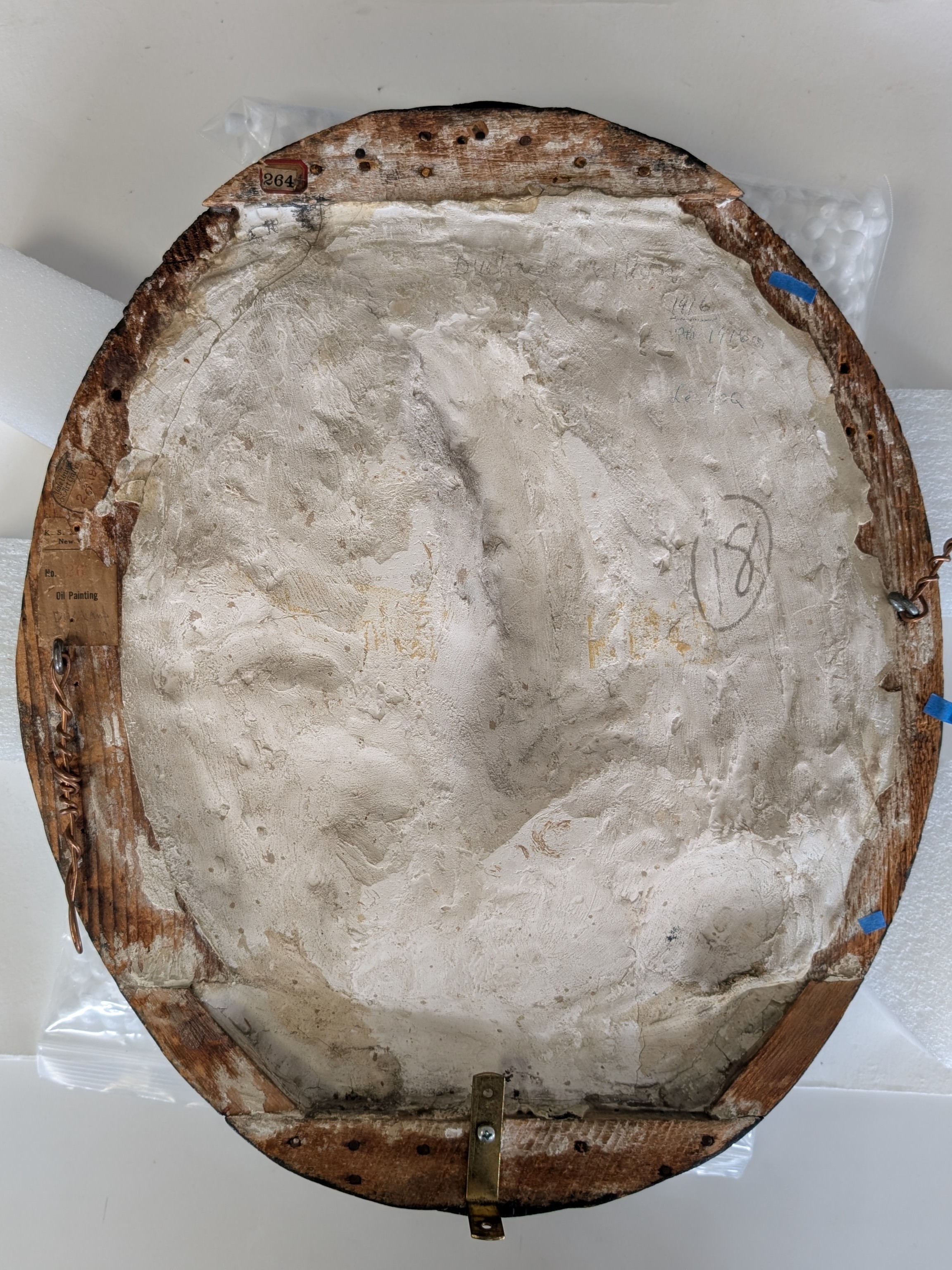

The opportunity to look at a work of art up-close, spending time with it, looking at areas that aren’t always visible, such as the reverse—these are some of my favorite things about being a conservator. In the case of Gallic Cock, the reverse provides information about how the work was made, its history, and its condition. (fig. 1)

Looking at the reverse, we see that the oval frame is constructed of multiple pieces of wood, something not evident when viewing the relief from the front. We also note the plant matter visible within the plaster. (fig. 2) Its presence gives us insight into the artist’s thought process as he created the relief—by including that material he made the plaster stronger, thus increasing the likelihood that it would withstand the frequent handling it was originally designed for as an ornament for a portable theater. The brushstrokes visible on the surface of the plaster give us an idea of at least one of the tools the artist used in creating the work.

Inscriptions and paper gallery labels on the reverse are akin to stamps in a passport, telling us where the artwork has traveled. Yellowed adhesive residue on the plaster suggests that other labels were attached in those places at one time.

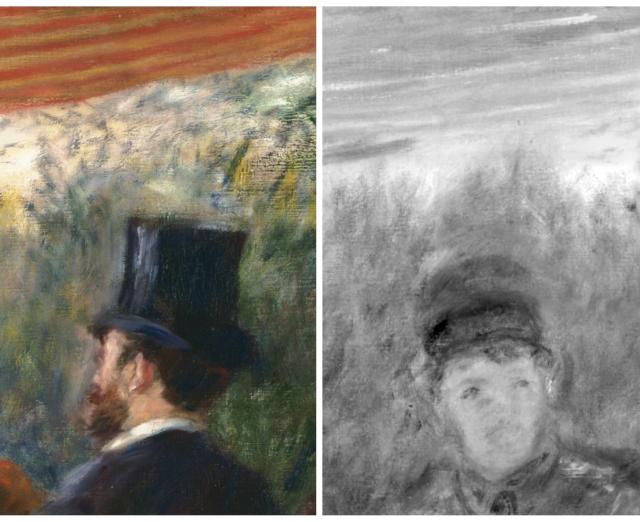

While examining Gallic Cock, I noted that the relief was in good condition overall, but that several cracks were present where the wood frame and the plaster meet. These are likely the result of dimensional changes in the materials in response to fluctuations in the environment over the course of the work’s lifetime. On the reverse, the presence of darkened glue around the cracks tells us this isn’t a recent issue.

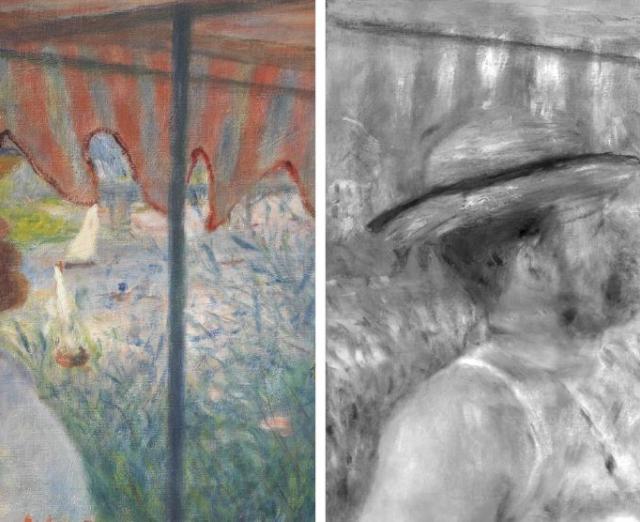

That discolored glue, however, pulled away from the surface as it aged, and it was no longer effective. This separation of the plaster from the wood meant that the relief could detach from the frame, with potentially disastrous consequences. My treatment, then, in addition to gently cleaning the surface on both the front and the reverse (fig. 3), included injecting a more stable, conservation-tested adhesive into cracks to improve the stability of the relief and ensure its longevity. (fig. 4)