Difficult Conversations

Reading the Black South from Aunt Clemmy to Charity

By Adrienne L. Childs

From the Seeing U.S. Research Project

“I decided to confront the challenges posed by a lesser-known artist in The Phillips Collection—Laura Douglas—and explore the possible counternarratives that other works in the collection by Walker Evans, Jacob Lawrence, and Joseph Holston can reveal.”

The Phillips Collection’s Seeing U.S. project’s exploration of lesser-known histories in its collection has proven to be a fascinating enterprise that has uncovered both compelling stories and uncomfortable truths. In recent years, art museums throughout the United States have taken to revisiting, reconsidering, and reinvigorating their permanent collections through new research, radical reinstallations, and innovative exhibitions. Curators, educators, and administrators are taking stock of what stories they have been telling and what they have not. These reconsiderations have emerged, in part, because museums have had a collective call to consciousness about prior exclusionary practices that have placed value on certain artists and artistic traditions at the expense of others. Still, questions abound. Who are the artists that have received the most attention? Whose work has fallen into the dark recesses of storage? What happens when we shed light on long-held objects that, upon further scrutiny, represent difficult histories? Museums are often confronted with the choice of engaging with works collected at a time when social consciousness about racism, sexism, and other social blind spots were not considered at all, or ignoring the troubling objects altogether. As a case study of one possible approach to this quandary, I decided to confront the challenges posed by a lesser-known artist in The Phillips Collection—Laura Douglas—and explore the possible counternarratives that other works in the collection by Walker Evans, Jacob Lawrence, and Joseph Holston can reveal.

Our intrepid Howard University fellow Rebecca Shipman conducted research on several artists in our collection that we wanted to learn more about and examine with renewed critical attention. Her archival research on painter Laura Douglas (1886–1962) uncovered a complex story of a female artist whose efforts and achievements in a male-dominated world were progressive but did not receive the acclaim she sought, and whose work was often mired in the entrenched racial biases and stereotypes of the segregated South. Douglas, who is represented by eight works in the Phillips, was born in Winnsboro, South Carolina, and as a professional artist fashioned herself as a true chronicler of the South. She had extensive art education training in Washington, DC, New York City, Paris, Munich, and Florence. She worked in an Expressionist style, and her approach to form was decidedly modernist in spirit. After spending several years studying and exhibiting in Europe, Douglas wanted to return to South Carolina to fulfill her wish to “do something of value” for her state.[1] She applied to the Federal Art Project (FAP) of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal program that employed artists across the country during the Depression.

In 1937, Douglas began work on a series of paintings that she hoped would “build up and preserve in paint the history of the State.” She declared that they would be a contrast to “arid towns, drought region[s], garages, factory steeples and severe churches of other sections.” Douglas was likely referring to Regionalist painters who focused on American cities, landscapes, and modern industrial vistas. (See examples in The Phillips Collection by Louis Michel Eilshemius and Stefan Hirsh.) Although trained in modernist aesthetic styles, Douglas resisted the images of American modernity. Instead, she considered her interpretations of the South as revealing a more majestic side of America. “We are a lyrical part of the country,” wrote Douglas, “and much of the old civilization is still here.” Because she was a South Carolinian, Douglas claimed to see the truth in her Southern subjects: cotton fields, red clay hills, Low Country landscapes, and “negro life.” In fact, Douglas was creating a series of works she called her “negro symphonies” that chronicled Black Southern life as she saw it.[2] Five of the works in The Phillips Collection represent Douglas’s view of the Southern “negro.” Aunt Clemmy, Symphony No. 2, Charleston, and Summerville, South Carolina present picturesque views of Black Southern culture but pose challenging questions about the artist’s point of view and her expressed desire to memorialize the Old South.

Laura Douglas, Aunt Clemmy, not dated, Opaque watercolor on paper, 16 1/2 x 12 1/2 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1944

Douglas was not alone in her interest in preserving the memory of the “old civilization” in the American South. In fact, since the post-Reconstruction era, a concerted effort grew across American cultural outlets to reify and mythologize the South in the service of post–Civil War reconciliation between North and South. This cultural trend aimed to rehabilitate the defeated region and fortify the culture of white supremacy on which it was built. Themes of the idyllic plantation days that depicted docile, happy, rural African Americans—both enslaved and free—were played out in literature, music, theater, and visual culture.

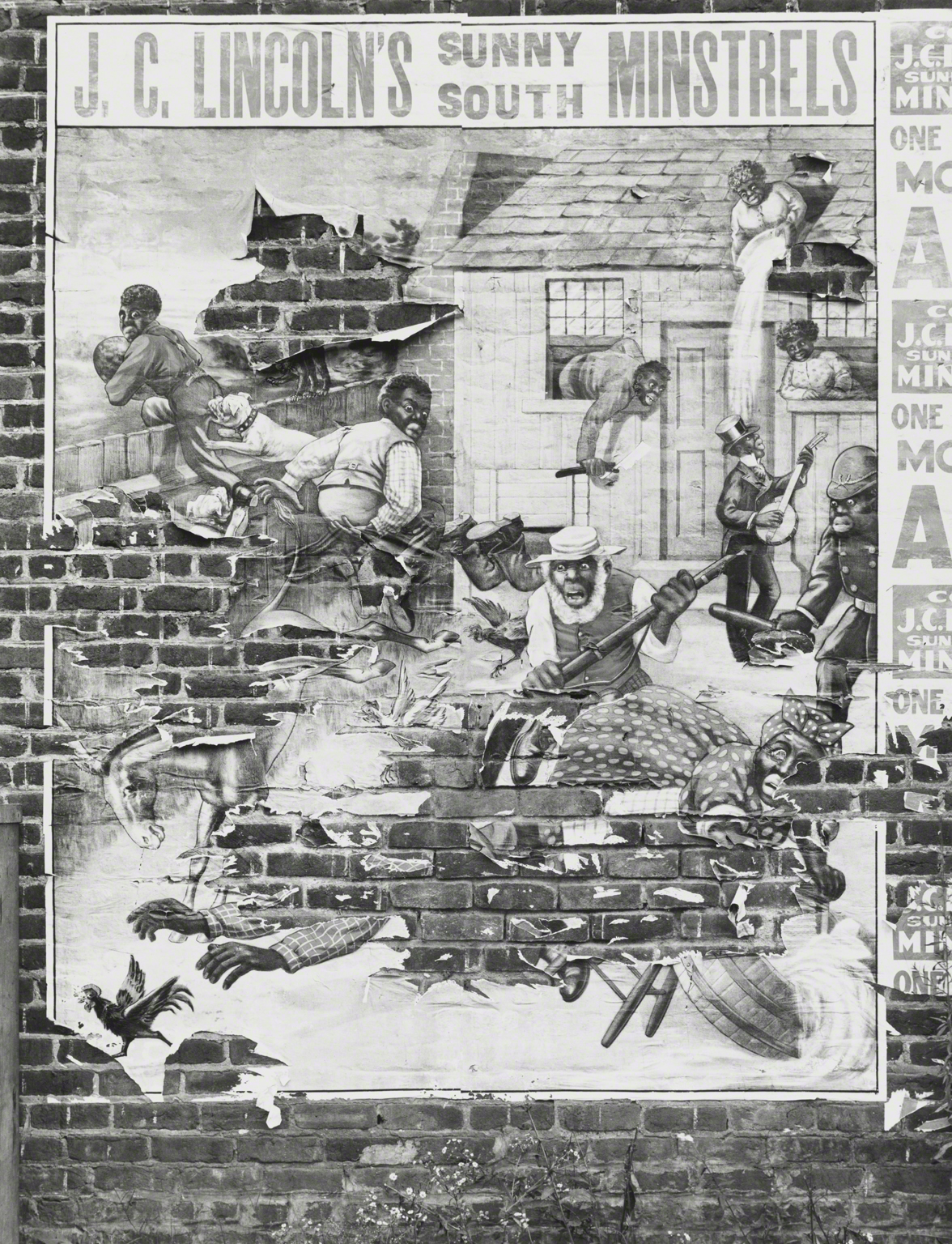

By the early 20th century an entire genre of both heroic and nostalgic views of the South flourished in American popular culture. Monuments to Confederate luminaries began to spring up across the country, largely supported by an organization of white women—the United Daughters of the Confederacy—who wanted to build a collective memory that glorified the Confederacy and all that it stood for.[3] Margaret Mitchell’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel Gone with the Wind, published in 1936, became a wildly popular book and later a film that mythologized Southern white womanhood and the gallantry of the Lost Cause while it naturalized stereotypes—most famously the Mammy. However, the Old South was a contested terrain. Walker Evans captured the irony of the racialized myths of the Old South in his 1936 photograph Minstrel Poster, Alabama, also in The Phillips Collection. Walker’s photo of a ripped and tattered advertisement for “J.C. Lincoln’s Sunny South Minstrels” captures the ways in which popular entertainment promoted the myths an Old South—hardly “sunny” and wholly dependent upon racial stereotype. The worn and perhaps intentionally torn state of the poster reflects how the mythologies of the Southern “Negro” were indeed in dispute and decay. Douglas’s works are part and parcel of the tensions inherent in the romanticization of the South.[4]

Walker Evans, Minstrel Poster, Alabama, 1936, Gelatin silver print, 15 7/16 x 11 7/8 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, 2018 (Gift of the Rev. Jo C. Tartt, Jr.)

Douglas’s painting Aunt Clemmy—undated but likely completed during her late-1930s sojourn in South Carolina—draws upon one of the most enduring and damaging stereotypes of Black womanhood: the Black Mammy. Aunt Clemmy is a representation of an elderly African American woman seated in an interior setting. Wearing a heavy coat over her clothing, she sits calmly with her large working-woman’s hands folded in her lap. Her white hair starkly contrasts with her dark skin, rendering them both more intense. Clemmy does not meet the viewer’s gaze but glances to the side. In many ways, Douglas’s depiction of Aunt Clemmy is sensitive and does not trade on the physical exaggerations typical of Mammy imagery. Indeed, unlike many paintings of Black subjects by white artists that do not identify the sitter, she is named. Yet it is that name—Aunt Clemmy—that ushers in a narrative of derogatory typologies and prompts us to rethink Douglas’s conceptualization of this elderly Black woman.

Douglas’s expressed goal was to preserve the history of the “negro.” But whose history is she preserving? In her preservation efforts Douglas chooses to represent Aunt Clemmy, who is a Mammy figure. The terms “Mammy” and “Auntie” were interchangeable, as they referred to Black women who served as domestic workers in the antebellum plantation system and beyond. Like the term Mammy, which evokes a surrogate mother, Auntie is an endearing term that also infers a familial relationship, but when bestowed upon an enslaved person it becomes a patronizing pet name. Mammys worked in kitchens and performed other household duties but were most remembered as wet nurses and caretakers for white children.[5] Stories of the beloved devotion of the Black Mammy to the white family abounded in histories and fictions of the American South.[6]

Douglas’s sentiments about Black Americans were clear. In her application to the FAP, Douglas wrote: “The negro is a primitive race, so I chose the cave drawings as my motive [motif], crude, lyrical.” Indeed, Symphony No. 2, Charleston depicts Black figures interacting in an open-air marketplace. The linear depictions of the figures mimic the prehistoric cave drawings to which she refers in her statement. In addition, the scene is fashioned with no perspective against a backdrop of earthen browns and grays that suggest a stone wall. Douglas’s attitudes toward Black people were not unusual, and depictions like these were accepted as examples of Regionalist views of American life. Duncan Phillips collected Symphony No. 2, Charleston in 1942 and Aunt Clemmy in 1944.

After identifying and acknowledging the issues posed by works like Aunt Clemmy, how, then, do we come to terms with their troubling histories while maintaining an appreciation for their merits and the slice of American art that they represent? One approach is to identify other works in the collection that can serve as counternarratives and fuel a broader discussion of art and representation around the issues. In the 1930s and 1940s, while Douglas was studying the old ways of Black life in South Carolina, the New Negro Movement, or Harlem Renaissance, was flourishing in New York, Chicago, Washington, DC, and other urban centers around the country. Black writers, artists, scholars, and other culture workers were creating progressive narratives that aimed to expressly denounce the caricature of the subservient and buffoonish “Old Negro” by depicting the modernity of Black life, much of which developed outside the South.[7] In many ways, Black cultural modernity was crafted in direct response to the imagery of Douglas and others who romanticized the South. Putting Douglas’s work in dialogue with alternative narratives of Black life helps to expand our understanding of a very complex era in America.

Interestingly, in 1942, the year he acquired Symphony No. 2, Charleston, Phillips also acquired half of Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series, seen by some as a masterwork embedded in the ethos of the Harlem Renaissance and a magisterial chronicle of the Great Migration. The multi-panel work charted the movement of Black people from the oppressive South to urban centers in the North during the early 20th century.[8] Lawrence’s vision of Black Southerners journeying north did not depict passive stereotypes but rather people actively engaged in changing their circumstances. With a spare, abstract style, Lawrence narrates Black south-to-north migration in a visual language that emphasizes its centrality to the story of American modernity—looking to the future, not the past. In this likely unintentional stroke, Phillips acquired works that reflect both the stagnation and the dynamic movement that characterized Black life in 20th-century Jim Crow America.

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, Black American artists have demonstrated the importance of representing the afterlives of slavery with their own voices. Dignified portrayals of Black ancestors from the South have been particularly important to artists who recognize the harmful effects of stereotypes and create their own narratives to dispel reductive mythologies. Joseph Holston’s 1976 etching Charity—also in The Phillips Collection—is an example of this impulse and demonstrates that the museum’s holdings can indeed provide a resonant counternarrative to Douglas’s Aunt Clemmy.

Joseph Holston, Charity, 1976, Etching, aqyiatint and embossing on paper, 11 3/4 x 8 5/8 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Joseph and Sharon Holston, 2014

Holston, a native of Washington, DC, has been a chronicler of Black life for more than 50 years. Charity, an etching, was based on a 1974 wash drawing that Holston sourced from a magazine image. When Holston’s mother saw the drawing, she said that it looked like Charity, a distant relative that she remembered from her childhood in Harriman, Tennessee. Holston’s family research has found that Charity was likely born enslaved around 1848, and by 1920, she is listed as a washerwoman.[9] While The Phillips Collection’s etching is not a portrait of Charity, it is a site of memory for Holston’s family. Naming the portrait Charity imbues the figure with history and identity stemming from the artist’s own ancestry. Holston’s approach to the seated elder is simple and elegant. Her face, lined with age and experience, peers at the viewer with a pleasant, knowing smile. Like Aunt Clemmy, Charity has white hair that contrasts with her dark skin and large hands, which speak to a lifetime of work. However, Holston’s reduced palette highlights Charity’s emotional expression of warmth and dignity while leaving the clothing, chair, and other details as sketches. The fact that Holston’s Charity gazes directly at the artist, while Aunt Clemmy averts her eyes, establishes a connection between the artist and, by extension, the viewer. Charity’s self-possession and sincerity reinforces her as a true subject rather than an object of observation. Holston’s dignified Charity, former slave and washerwoman, is most certainly an intentional subversion of the Mammy trope. Here the subtle gestures of creative work can shift perspectives.

For more than 100 years, the Phillips has been collecting modern and contemporary art that speaks to the aesthetic and social concerns of practicing artists. The collection allows the museum to chart more than a century of social and cultural changes through visual art. Placing works by Walker Evans, Jacob Lawrence, and Joseph Holston in conversation with those of Laura Douglas complicate and enhance the stories The Phillips Collection can tell about the shifting attitudes toward race in the United States. As co-curator of Seeing U.S., I feel that revealing and taking stock of the biases embedded in parts of the collection ultimately frees it to reflect more accurately the complex and sometimes messy, but ultimately captivating, history of America.

[1] Laura Douglas application to the Federal Art Project. Phillips Collection Archives.

[2] Douglas application to FAP.

[3] Roger C. Hartley, Monumental Harm: Reckoning with Jim Crow Era Confederate Monuments (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2021), 24–52.

[4] For more on the mythology of the Old South, see Tamara McPherson, Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender, and Nostalgia in the Imagined South (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2023), and Karen L. Cox, Dreaming of Dixie: How the South was Created in American Popular Culture (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013).

[5] Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008), 4.

[6] For more on the Mammy myth, see Wallace-Sanders, Mammy; and Jo-Ann Morgan, “Mammy the Huckster: Selling the Old South for the New Century,” American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 1995): 86–109.

[7] Alain Locke’s 1925 anthology The New Negro famously characterizes this movement as it developed in the 1920s. See Locke, ed., The New Negro: An Interpretation (Mansfield Center, CT: Martino Publishing, 2015).

[8] Leah Dickerman and Elsa Smithgall, eds., Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2015).

[9] Sharon Smith Holston, email to the author, October 19, 2023. Holston’s identification of the original source as a drawing corrects his prior statement published in Seeing Differently: The Phillips Collects for a New Century (Washington, DC: The Phillips Collection, 2021), which claims the etching was based on an oil painting.