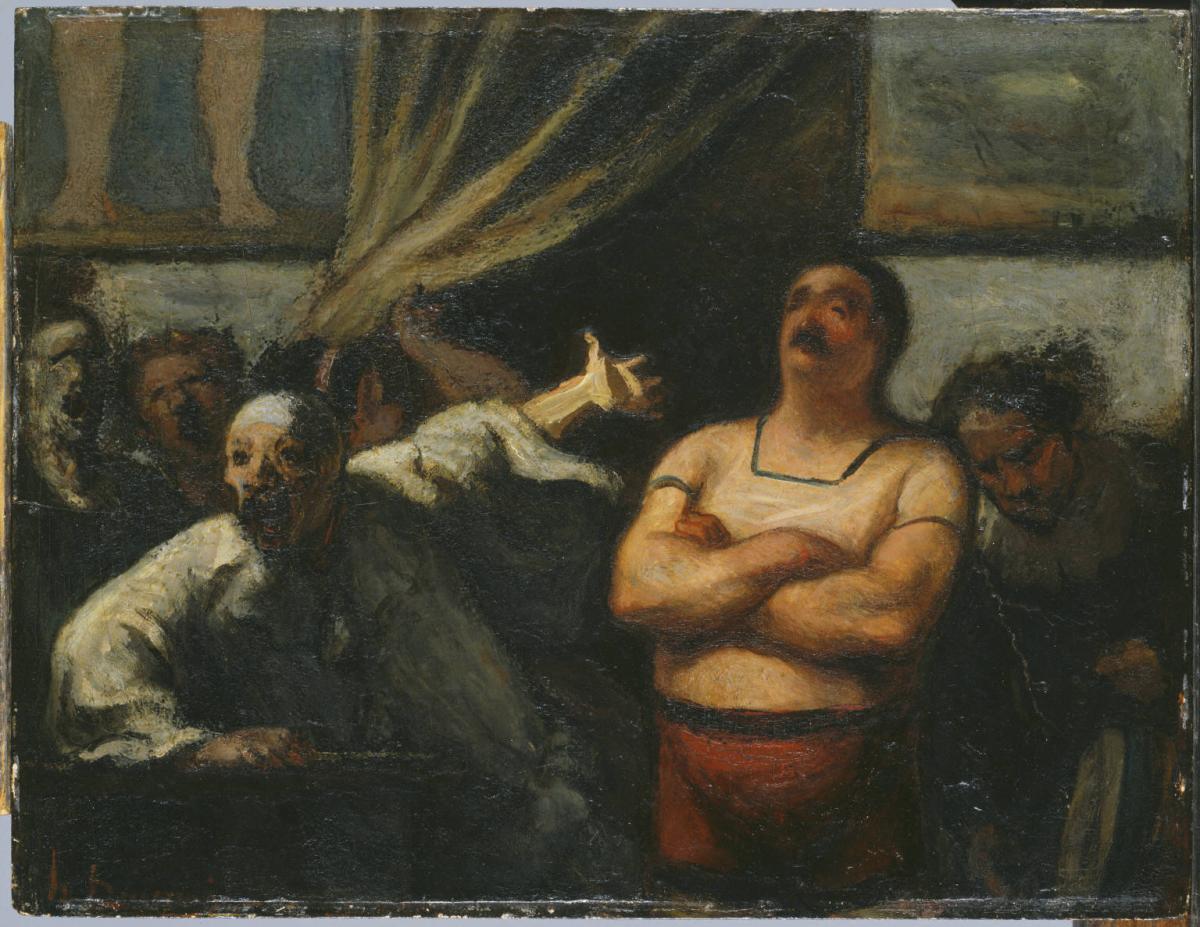

The Strong Man

Honoré Daumier ( c. 1865 )

The Strong Man is related to two crayon sketches of the barker and a charcoal study of the strongman. In the present work these figures join others to form a complex composition. The subject is a parade, or sideshow, in which clowns, musicians, barkers, and strongmen perform before a theater or tent to solicit customers for the spectacle within. These shows were popular during the eighteenth century in connection with Commedia dell’ Arte performances at fairs. By the time Daumier painted most of his parade pictures, in the 1860s, they were no longer a common feature of the Paris scene, although they could still be found in the temporary fairgrounds set up during festivals.

Sharp light illumines the strongman, whose relatively warm colors set him in striking relief to the subdued gray and blue tones of the rest of the image. His muscular, barrel-chested body contrasts with the backdrop, which consists of flat, rectilinear sections; a pair of legs in the upper left appears to be part of a poster advertising one of the acts. A clown-like barker exhorts the crowd to notice the proud “Hercules.” His stentorian claims are emphasized by his bold gesture and punctuated by his dramatically lit hand, in the center of the composition. The spectral faces of the barker and the open-mouthed figures behind him are grotesque, giving the scene an intensely expressionistic quality.

While Daumier’s earlier depictions of parades often lampoon their persistent, frenzied hawking, his works from the 1860s exaggerate to the point that they assume a demonic, nightmarish aspect. It has been suggested that because he was forbidden by censorship laws to caricature French politicians, Daumier may have expressed his dislike of Louis Napoleon and his propaganda machine in more oblique ways. There is reason to believe that the Phillips picture may thus constitute a work of social commentary in which the metaphor of the sideshow is used to condemn the “propaganda activities of the Age of the Empire which deftly assessed and manipulated the new political weapon of the era—public opinion.”