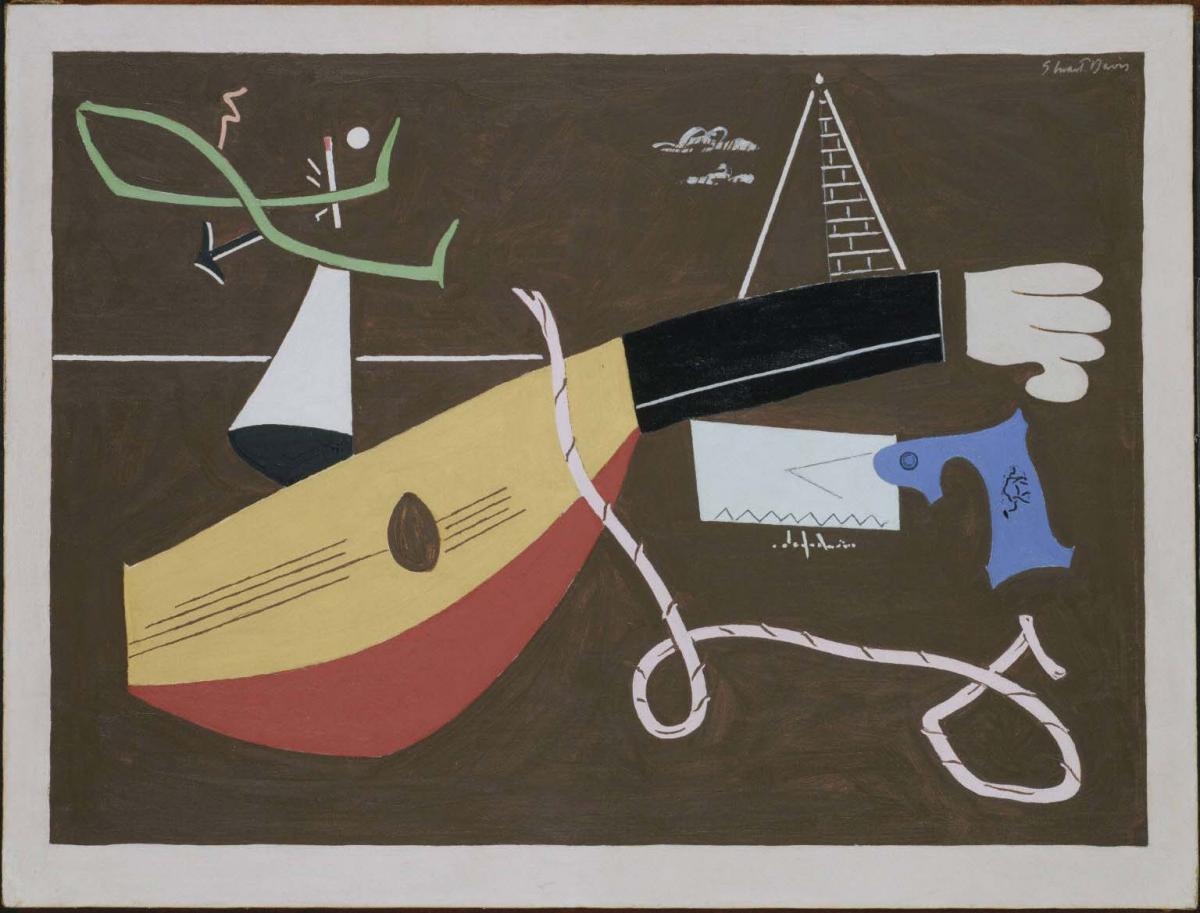

Still Life with Saw

Stuart Davis ( 1930 )

Stuart Davis painted Still Life with Saw after his return from Paris. His goal was to juxtapose American and Parisian imagery against a vague and undefined background. In Still Life with Saw, a large mandolin is suspended against an ambiguous setting in the company of workman’s tools: a handsaw, a length of rope, and a pair of tongs. Spatial ambiguity is created by the white lines in the background which could either be a horizon line or a table edge. The stark contrast between a musical instrument suitable for an elegant drawing room and rugged implements used for manual labor render it one of the artist’s most surreal, enigmatic works.

By emphasizing the scale of the mandolin, yet having the title allude to the less prominent saw, Davis is proving that regardless of the purpose of an object, it is still worthy of art. Davis might have been making a tongue-in-cheek allusion to the comment by formalist art critic Clive Bell, who wrote that a person with no sense of aesthetics has “no faculty for distinguishing a work of art from a handsaw” and “is apt to rear up a pyramid of irrefragable argument on the hypothesis that a handsaw is a work of art”. Perhaps Davis was seeking to debunk such an assumption. The fact that the saw is given equal billing with the mandolin and even appears to threaten it with its emphatic jagged teeth possibly reflects the artist’s opinion that utilitarian, everyday objects are as worthy of representation as traditionally used cubist motifs.

InStill Life with Saw, Davis altered motifs and techniques from surrealism and cubism to suit his personal style. The objects’ identities are readily recognizable, even highlighted in their individuality, though their purpose within the context of the painting remains ambiguous. Such demonstrations of Davis’s artistic agility and clever nature, coupled with his struggle to maintain his originality in the face of European art movements, were appreciated by Duncan Phillips. As he wrote in the essay “Modern Wit in Two-Dimensional Design,” which accompanied his 1931 exhibition of the same title, “No one can say that [Davis] is not strikingly a man of his time and…of witty ideas on his own account.”