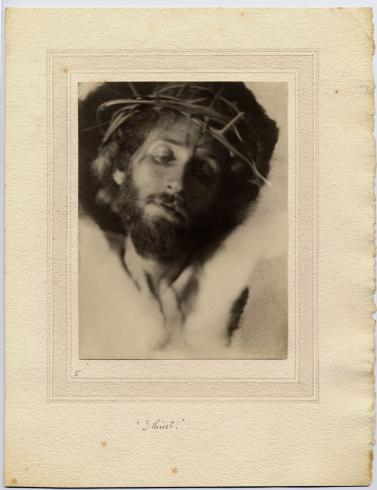

Truth Beauty

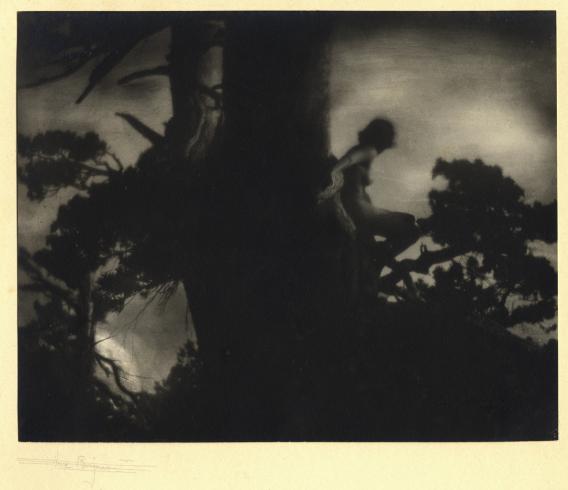

Pictorialism and the Photograph as Art 1845–1945

Photographic pictorialism, an international movement, a philosophy, and a style, developed toward the end of the 19th century. The introduction of the dry-plate process, in the late 1870s, and of the Kodak camera, in 1888, made taking photographs relatively easy, and photography became widely practiced.

About the Exhibition

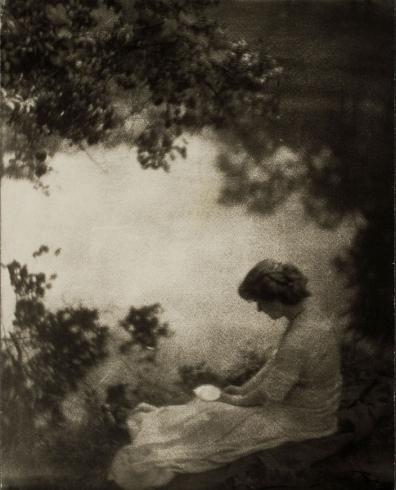

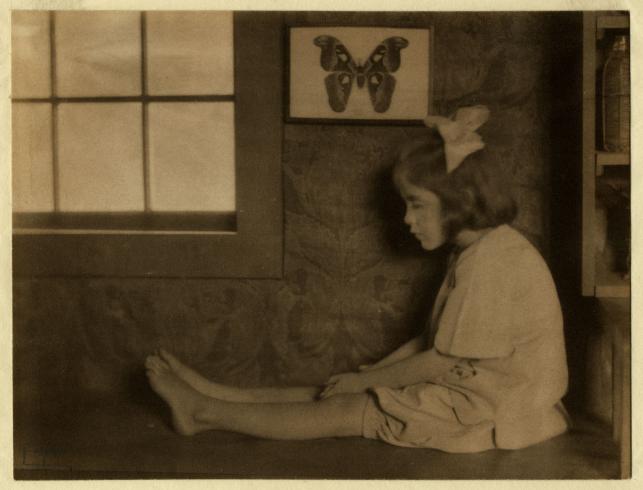

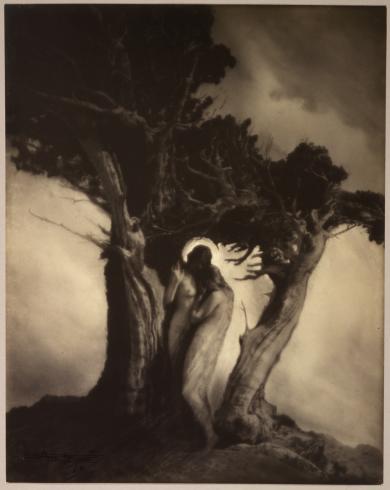

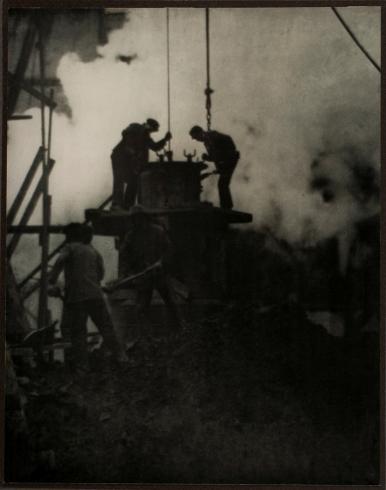

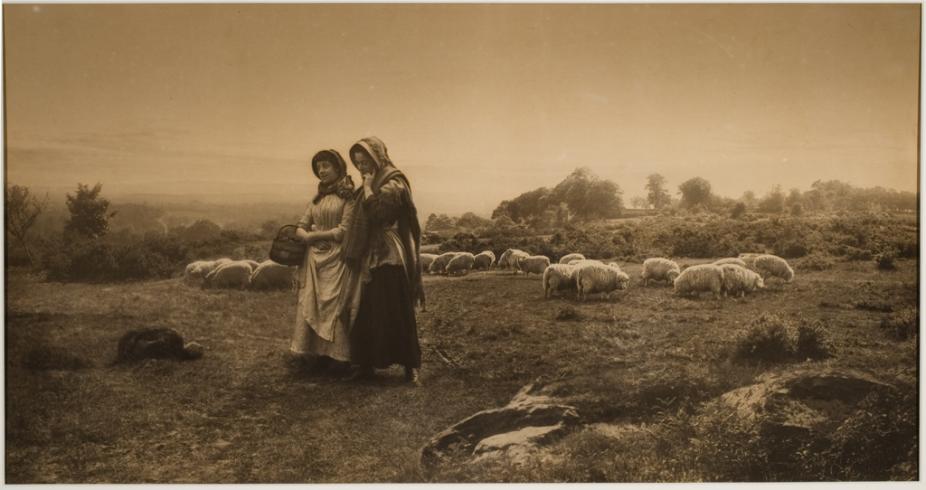

Photographic pictorialism, an international movement, a philosophy, and a style, developed toward the end of the 19th century. The introduction of the dry-plate process, in the late 1870s, and of the Kodak camera, in 1888, made taking photographs relatively easy, and photography became widely practiced. Pictorialist photographers set themselves apart from the ranks of new hobbyist photographers by demonstrating that photography was capable of far more than literal description of a subject. Through the efforts of pictorialist organizations, publications, and exhibitions, photography came to be recognized as an art form, and the idea of the print as a carefully hand-crafted, unique object equal to a painting gained acceptance.

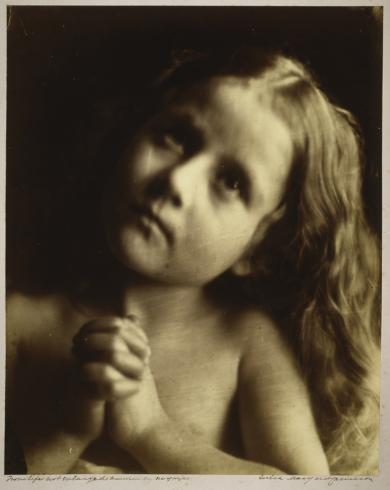

The forerunners of pictorialism were early photographers like Henry Peach Robinson and Julia Margaret Cameron. Robinson found inspiration in genre painting; Cameron’s fuzzy portraits and allegories were inspired by literature. Like Robinson and Cameron, the pictorialists made photographs that were more like paintings and drawings than the work of commercial portraitists or hobbyists. Pictorialist images were heavily dependent on the craft of nuanced printing. Some photographers, like Frederick H. Evans, a master of the platinum print, presented their work like drawings or watercolors, decorating their mounts with ruled borders filled with watercolor wash, or printing on textured watercolor paper, like Austrian photographer Heinrich Kühn. Kühn achieved painterly effects by using an artist’s brush to manipulate watercolor pigment, instead of silver or platinum, mixed with light-sensitized gum arabic.

The idea that the primary purpose of photography was personal expression lay behind pictorialism’s “Secessionist” movement. Alfred Stieglitz’s “Photo-Secession” was the best-known secessionist group. Stieglitz and his magazine, Camera Work, with its high-quality photogravure illustrations, advocated for the acceptance of photography as a fine art.

Early in the 20th century, pictorialism began losing ground to modernism: in 1911, Camera Work published drawings by Rodin and Picasso, and its final issue, in 1917, featured Paul Strand’s modernist photographs. Nevertheless, pictorialism lived on. A second wave of pictorialists included Clarence H. White, whose students included such photographers as Margaret Bourke-White, Paul Outerbridge, and Dorothy Lange. White’s colleague, Paul Anderson, continued the pictorial tradition until his death in 1956. Five prints of his Vine in Sunlight, 1944, display five different printing techniques, demonstrating how each process subtly shapes the viewer’s response to the image.

Organized by George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film, and Vancouver Art Gallery.