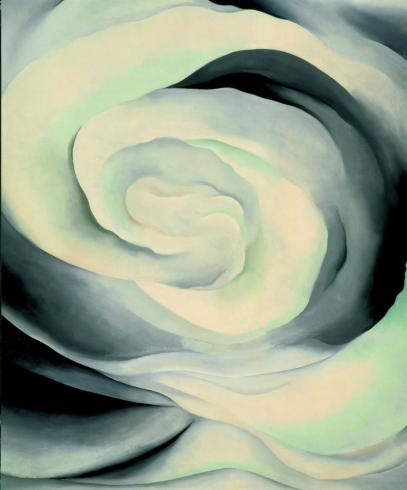

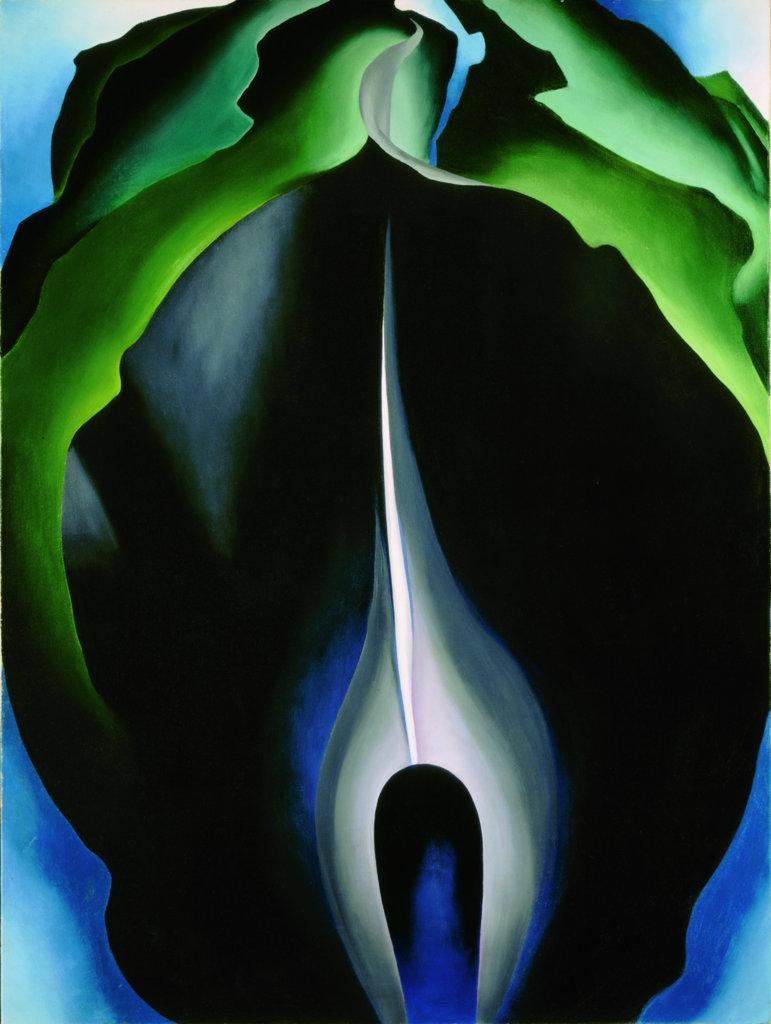

Georgia O’Keeffe

Abstraction

Although best known for her iconic representations of flowers, landscapes, and animal bones, Georgia O’Keeffe’s abstract work is as bold and breathtaking as that of her European contemporaries Picasso, Matisse, and Kandinsky. See an American legend in a whole new light in this exhibition of over 100 paintings, drawings, and watercolors.

About the Exhibition

Although painter Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), a central figure in 20th-century art, is best known for simplified images of recognizable objects, her contributions to American abstraction over the course of her long career were radical. Her approach—in paintings, drawings, and watercolors—was determined in 1915, when she decided that her art would record her feelings, rather than the appearance of things. For the remainder of her career, she looked to art, whether abstract or objective, to express emotions for which words seemed inadequate.

In her first abstractions, a series of non-objective charcoal drawings, O’Keeffe reduced her palette to black and white. She filled her compositions with fluid, curvilinear forms reminiscent of Art Nouveau. In 1916, responding to the elemental landscape of western Texas, O’Keeffe reintroduced color into her watercolors. By magnifying and tightly cropping her images, a framing device used by photographers, she found the means to express simultaneously the vastness of nature, the immensity of her own response to it, and a powerful sense of being one with it. Two years later, seeking recognition as a painter in the circle of modern art dealer and photographer Alfred Stieglitz, she moved to New York and took up oils again.

Unwelcome critical interpretations of her work as expressive of her sexuality and a limited market for abstraction led O’Keeffe to turn away from pure abstraction in the 1920s and 1930s. After 1923, she rarely showed her early abstractions. Indeed, between 1935 and 1941, she produced no abstractions at all. Beginning in 1929, O’Keeffe spent long stretches of time in New Mexico, finally moving there in 1949. It proved to be an inexhaustible source of subjects for her mature works. She approached these as she had her most abstract works, through her feelings, using many of the same stylistic means. As she said, “I had to create an equivalent for what I felt about what I was looking at-not copy it.”

Likely stung when critic Clement Greenberg trounced her in 1940 for having chosen representation over abstraction, O’Keeffe returned to it in 1942, painting forms she found in the natural world that corresponded to abstract forms in her imagination. With the market more receptive to abstract art, she began to exhibit her abstractions again. By the late 1950s and 1960s she was working almost exclusively in an abstract style, in mural-sized aerial views of clouds and a minimalist, geometric series of patio door paintings. The fields of color of her radical late works set a precedent for a younger generation of abstract artists in the 1960s.

Included in the exhibition are more than 100 paintings, drawings, and watercolors by O’Keeffe, dating from 1915 to the late 1970s, and 12 photographic portraits of her by her husband, Alfred Stieglitz.