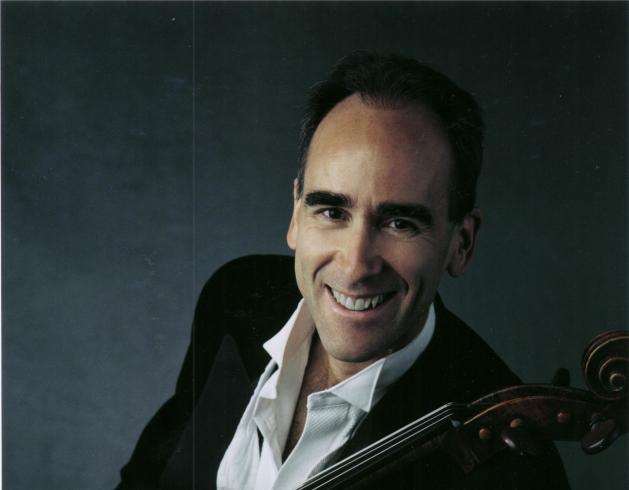

Carter Brey & Benjamin Pasternack

Cello and Piano

Carter Brey and Benjamin Pasternack will make their Phillips debut with selections by Robert Schumann, Leonard Berstein, Elliot Carter, Leon Kirchner, and Frédéric Chopin.

Program

Carter Brey has been principal cellist of the New York Philharmonic since 1996. In 1981 he was a prizewinner in the Rostropovich International Cello Competition, and he has appeared as a soloist with most of America’s leading orchestras. He has also performed with the Emerson and Tokyo string quartets and given recitals with celebrated pianists. Benjamin Pasternack, a graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music who now sits on the piano faculty at Peabody Conservatory, regularly performs with symphonies and chamber musicians on multiple continents. Brey and Pasternack share a special affinity for American music, reflected in this concert with major works by Elliott Carter and Leon Kirchner as well as Pasternack’s own Bernstein arrangement alongside Romantic masterpieces by Schumann and Chopin.

PROGRAM:

ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856)

Fantasiestücke, Op.73 (1849)

Zart und mit ausdruck

Lebhaft, leicht

Rasch und mit Feuer

LEONARD BERNSTEIN (1918-1990)

Transcribed for Piano by Benjamin Pasternack

Three Dance Episodes from On the Town (1945)

The Great Lover

Lonely Town

Times Square 1944

ELLIOTT CARTER (1908-2012)

Sonata for Cello and Piano (1948)

Moderato

Vivace, molto leggiero

Adagio

Allegro

Intermission

LEON KIRCHNER (1919-2009)

For Solo Cello (1986)

FRYDERYK CHOPIN (1810-1849)

Sonata for Cello and Piano in g minor, Op. 65

Allegro moderato

Scherzo: Allegro con brio

Largo

Finale: Allegro

About the Artists

Carter Brey was appointed Principal Cellist of the New York Philharmonic in 1996 and made his subscription debut as soloist with the Orchestra in May 1997, performing Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations led by then-Music Director Kurt Masur. He has performed as soloist in subsequent seasons in the Elgar Cello Concerto with André Previn conducting, in William Schuman’s A Song of Orpheus with Christian Thielemann, in Samuel Barber’s Cello Concerto with conductor Alan Gilbert, in Richard Strauss’s Don Quixote with Music Director Lorin Maazel and former Music Director Zubin Mehta, in the Brahms Double Concerto with Concertmaster Glenn Dicterow and conductor Christoph Eschenbach, as well as with Lorin Maazel on the orchestra’s 2007 tour of Europe. The Brahms was also performed at the Tanglewood Music Center in the summer of 2002 as part of Kurt Masur’s final concerts as Philharmonic Music Director. (Brey most recently performed Boccherini’s Cello Concerto in D Major with Riccardo Muti conducting in April of 2010.)

Brey rose to international attention in 1981 as a prizewinner in the Rostropovich International Cello Competition. Subsequent appearances with Mstislav Rostropovich and the National Symphony Orchestra were unanimously praised. His awards include the Gregor Piatigorsky Memorial Prize, the Avery Fisher Career Grant, and Young Concert Artists’ Michaels Award. He was the first musician to win the Arts Council of America’s Performing Arts Prize. Brey has performed as soloist with many of America’s major symphony orchestras.

His chamber music career is equally distinguished. He has made regular appearances with the Tokyo and Emerson string quartets as well as the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, the Spoleto Festival in the US and Italy, and the Santa Fe Chamber Music and La Jolla Chamber Music festivals, among others. He presents an ongoing series of duo recitals with pianist Christopher O’Riley; together they have recorded The Latin American Album, a disc of compositions from South America and Mexico (Helicon Records). His recording with Garrick Ohlsson of the complete works of Chopin for cello and piano was released by Arabesque in fall 2002 to great acclaim. A faculty member of the Curtis Institute, Brey appeared as soloist with the Curtis Orchestra at Verizon Hall and Carnegie Hall in April of 2009.

Brey was educated at the Peabody Institute, where he studied with Laurence Lesser and Stephen Kates, and at Yale University, where he studied with Aldo Parisot and was a Wardwell Fellow and a Houpt Scholar.

Among the most experienced and versatile musicians today, the American pianist Benjamin Pasternack has performed as soloist, recitalist, and chamber musician on four continents. His orchestral engagements have included appearances as soloist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Orchestre Symphonique de Québec, the Tonhalle Orchestra of Zurich, the New Japan Philharmonic, the Pacific Symphony, the New Jersey Symphony, the Orchestre national de France, the SWR Orchestra of Stuttgart, the Bamberg Symphony, and the Dusseldorf Symphony Orchestra. Among the illustrious conductors with whom he has collaborated are: Seiji Ozawa, Erich Leinsdorf, David Zinman, Gunther Schuller, Leon Fleisher, and Carl St. Clair. Pasternack has performed as soloist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra while on tour at Carnegie Hall and the Kennedy Center, as well as at concerts in Athens, Salzburg, and Paris on the BSO’s European tour of 1991, and in São Paulo, Buenos Aires, and Caracas on their South American tour of 1992. He has been guest artist at the Tanglewood Music Center, the Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto, Italy, the Seattle Chamber Music Festival, the Minnesota Orchestra Sommerfest, the Festival de Capuchos in Portugal, and the Festival de Menton in France, and has been featured as soloist twice on National Public Radio’s nationally-syndicated show SymphonyCast.

A native of Philadelphia, Pasternack entered the Curtis Institute of Music at the age of thirteen, studying with Mieczyslaw Horszowski and Rudolf Serkin. He was the Grand Prize winner of the inaugural World Music Masters Piano Competition held in Paris and Nice in July 1989. Bestowed by unanimous vote of a distinguished panel of judges, the honor carried with it a $30,000 award and engagements in Portugal, France, Canada, Switzerland, and the US. An earlier competition victory came in August 1988 when he won the highest prize awarded at the Fortieth Busoni International Piano Competition. After 14 years on the piano faculty of Boston University, he joined the piano faculty of the Peabody Conservatory of Music in September 1997.

Notes

Robert Schumann, Fantasiestücke, Op. 73 (1849)

In his late thirties, when he was already a well-established composer, Robert Schumann considered it his duty to help improve the quality of Hausmusik, or chamber music, played in German middle-class residences. In particular he was drawn to composing works for wind instruments whose solo repertoire was still somewhat limited. Thus in 1849 he composed his Adagio and Allegro for horn, his Three Romances for oboe, and his Fantasiestücke—all in the space of what was one of the most productive years of his entire career. To increase the appeal of these works, he allowed each work to be played on instruments other than the ones for which they were initially conceived; thus, he made Op. 73 available in versions for violin and cello in addition to the original form for clarinet.

These three fantasy pieces—in turn dreamy, lighthearted, and fiery—show Schumann’s supreme gifts as a writer of expressive melodies. Allusions to the style of his great art songs abound as the solo instrument—whatever it happens to be—pours out its musical soul against an active and technically demanding piano accompaniment.

Leonard Bernstein, Three Dance Episodes from On the Town (1945)

Transcribed for piano by Benjamin Pasternack

Bernstein’s fame writing Broadway shows grew simultaneously with his career as a classical conductor and concert composer. The ease with which he moved back and forth between popular and serious music set him apart from contemporaries in either field. He was, quite simply, a genius for whom conventional divisions and distinctions between “high” and “low” forms of music had little significance.

Bernstein wrote the musical On the Town in 1944, shortly after his first symphony, Jeremiah. This time the 26-year-old composer tackled a subject that was definitely non-biblical: three sailors on shore leave decide to sink their teeth into the Big Apple; not surprisingly, as they explore the sights of New York they also discover romance. (The plot has some similarities with Bernstein’s ballet Fancy Free, written earlier in the same year, but musically the two works are unrelated.)

Bernstein himself insisted that “the subject matter was light, but the show was serious.” He was referring to the show’s musical sophistication, which far exceeded previous Broadway practice. Dissonances that one would think are at home only in modern “classical” music blend easily with Bernstein’s dynamic, jazz-influenced musical idiom.

The Three Dance Episodes begin with The Great Lover, based on the musical’s hit song “New York, New York.” The three newcomers take a look around the city and begin to savor all that it may offer. In Lonely Town, the show’s major lyrical song, the sailor Gabey grieves over not finding that special someone without whom even a big city can seem empty and desolate. Times Square 1944 is based on the tune “I Get Carried Away,” a comic duet originally sung by the show’s two lyricists Betty Comden and Adolph Green.

Elliott Carter, Sonata for Cello and Piano (1948)

Elliott Carter, one of the leading musical modernists of the second half of the 20th century (and the beginning of the 21st), developed his avant-garde style gradually over the years. A former student of the legendary Nadia Boulanger, who was a close friend of Stravinsky’s, Carter started his career as a Neoclassical composer, with his ballet Pocahontas and the Symphony No. 1, among others. Around the time he turned 40, he began to search for untrodden paths in composition, and discovered entirely new ways to organize the rhythmic and harmonic aspects of his music. For the rest of his long life, he remained committed to a complex and challenging, yet at the same time highly expressive style that by no means excluded playful or light-hearted elements.

One of the first works in which Carter’s new orientation became manifest was the Cello Sonata, written in 1948 for the great American cellist Bernard Greenhouse, who gave the first performance with pianist Anthony Makas at Town Hall, New York, in 1950.

In his book on Carter’s music, composer David Schiff notes that in the four-movement sonata, “each movement begins with the transformation of musical ideas from the end of the previous movement,” resulting in a kind of circular design.

The composer himself offered the following comments about his work:

“After the first measure, the piano starts a regular beat, like a clock ticking, against which the cello plays an expressive melodic line in an apparently free manner without any clear coordination with the piano beat. This establishes two completely different planes of musical character. The entire form of this piece then consists of bringing these two instruments into various relationships with one another. There are developments, continuations, of this contrast between the two instruments, not, in this particular case, so much in terms of intervallic structure, but more in oppositions of character. So the piano and the cello are kept distinct throughout most of this work. I don’t know how the conception ever originated; it was actually the first time I had ever had the idea. I carried it out much further in 1951 in my First String Quartet and then in subsequent works, but the Cello Sonata was the first time I tried to make a piece that had two contrasting aspects that could be heard as one totality.”

The complex rhythmic divisions and the ways in which the two contrasting “planes” interact pose enormous challenges for the players; those challenges generate a sense of excitement that keeps listeners on the edge of their seats, never knowing what may happen next. (Many years later, Carter gave his only opera the title What Next?) The long melodic lines and the powerful rhythmic impulses represent two emotional worlds, and only the very last measures will tell which one gets the upper hand.

Leon Kirchner, For Cello Solo (1986)

Leon Kirchner, who had studied with Arnold Schoenberg in Los Angeles, was for many years a highly respected professor of composition at Harvard University, as well as an active conductor and pianist. The Pulitzer Prize, which he received for his String Quartet No. 3 in 1967, was just one among his many honors and awards.

Kirchner never forgot that his teacher was not only the initiator of the twelve-tone technique but also the father of musical expressionism. For both Schoenberg and Kirchner, atonality was never just an abstract exercise but rather a means to say things that had not been said before. John Adams, who had studied with Kirchner at Harvard, said of his teacher: “[He] was one of the most intuitive musicians I ever encountered…[He] could never find a way to make his own musical instincts fit into the straitjacket of a rigorous method.” Elsewhere, Adams commented: “What makes his music lasting in my mind are those great exploding arches of counterpoint and the erotic lushness of the harmonies.”

The qualities praised by Adams (even the harmonies and counterpoint) are on full display in Kirchner’s piece for unaccompanied cello, which was premiered by Carter Brey at the Spoleto Festival in Charleston, South Carolina, on May 28, 1988. The work was originally written for violin, as the required new work for the Indianapolis Violin Competition. It was Yo-Yo Ma (another former Kirchner student) who gave the composer the idea of making a cello version of the piece. The published score of For Cello Solo was dedicated “to Carter and Yo-Yo.” Later Kirchner joined the work with two duos for violin and cello and called the resulting three-movement composition Triptych.

One way of listening to For Cello Solo is to approach it as a series of gestures, where the soloist, like a traveler, traverses a wide range of emotional territory, from rugged mountain chains to calm open fields. High and low registers, fast runs and expansive melodic lines, double stops, harmonics, and pizzicatos (plucked notes) are all part of a large vocabulary, which is used to tell a fascinating and compelling story without words.

Fryderyk Chopin, Sonata for Cello and Piano in G minor, Op. 65 (1845-46)

One of the few works by Chopin to involve another instrument besides the piano, the cello sonata owes its existence to a friend of the composer’s named Auguste Franchomme, an outstanding cellist who became professor at the Paris Conservatoire in 1846, the very year the sonata was completed.

The work caused Chopin a great deal of trouble. He made more sketches for it than for any other and rejected many preliminary versions before arriving at the final form. It remained the last major work Chopin’s failing health allowed him to complete. The multi-movement sonata cycle was not Chopin’s natural way of expression, and he had to work especially hard to make his ideas fit into a large-scale musical structure. Being “in the moment” was clearly more important to him than moving toward a specific goal like Beethoven and the German-speaking composers who followed him. He molded the classical sonata form to suit his specific needs: in the recapitulation of the first movement; he did not bring back any themes from the exposition that he had used in the development. By so doing, he turned the entire second half of the movement into a free, fantasy-like recomposition of the first half.

The second movement is a vigorous Scherzo with a tenderly singing middle section, while the third-movement Largo, despite its brevity, brings the work to an emotional high point. The two instruments take turns playing a theme of heavenly beauty. The musical gestures of the Finale, according to leading Chopin authority Jim Samson, “sound like unmuted responses to Mendelssohn and even Schumann, for all Chopin’s professed dislike of their music.” What makes Chopin’s finale somewhat “Germanic” is precisely that relentless forward drive, mentioned above, that Chopin tended to avoid elsewhere—though even here he tempered it by extended lyrical episodes. The dramatic tensions are dispelled at the end by a switch to G Major and a radiant coda.

On February 16, 1848, Chopin and Franchomme played the second, third, and fourth movements of the Cello Sonata at a concert in Paris. It was to remain Chopin’s last performance in the city where he had made his home for 16 years. In the summer he completed a successful concert tour in England and Scotland. Yet by November 1848 his health had taken a turn for the worse. No longer able to perform or teach, he managed only a few brief compositional sketches before his death on October 17, 1849, at age 39.

Peter Laki, 2016