Georges Braque

and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945

It is not enough to make people see the object you paint. You must also make them touch it.—Georges Braque (1882–1963)

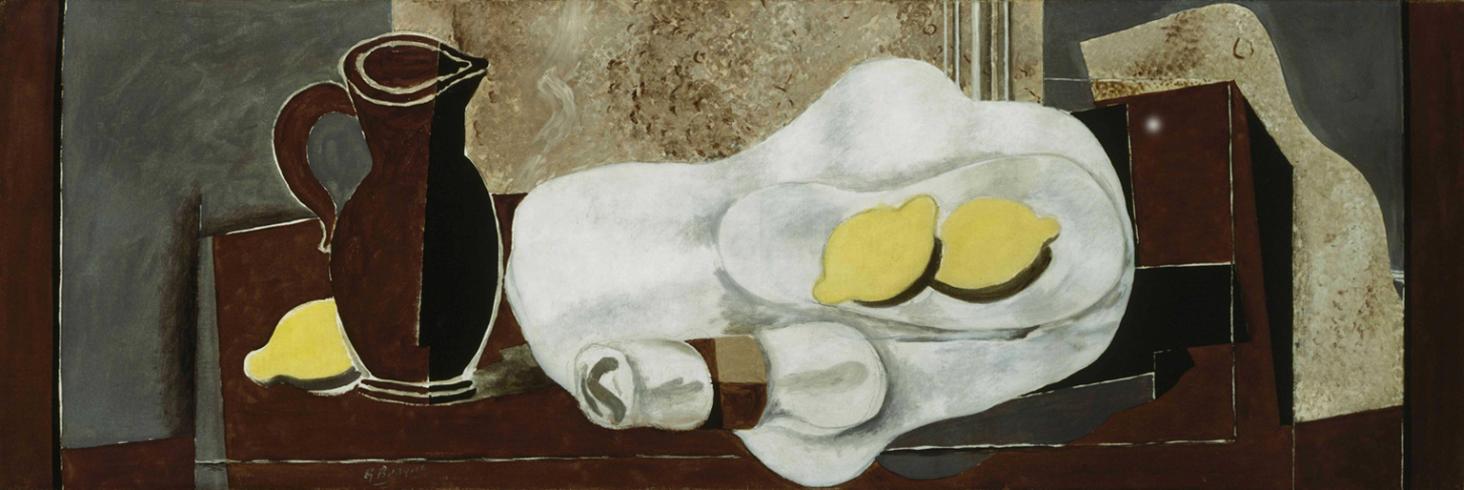

In the early 20th century, when Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso pioneered the new pictorial language of cubism, they profoundly affected the course of modern art. Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945 is the first in-depth look at the years leading up to and through World War II, a period in Braque’s career when he used the theme of still life to synthesize cubist discoveries and hone his individual style. Forty-four sumptuous canvases, along with related objects, trace the artist’s journey from painting still lifes in intimate interiors in the late 1920s, to vibrant, large-scale spaces in the 1930s, to more personal interpretations of daily life in the 1940s. The works, drawn from collections in America and Europe, are framed within the political and historic context of the time.

Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945 brings together for the first time in 80 years the Braque paintings known as the Rosenberg Quartet (1928–29). Used as models for marble panels in the Paris apartment of Braque’s art dealer Paul Rosenberg, the four canvases reveal aspects of Braque’s process; all were in his studio at the same time at various stages of completion, as he reworked them over several years. Other paintings show Braque’s interest in conveying the physicality of objects and surrounding space. In The Pink Tablecloth (1933) and Fruit, Glass, and Mandolin (1938), Braque added powdered quartz and sand to a white ground to evoke intricate textures. In Still Life on a Red Tablecloth (1934), painted and incised patterns provide surface variation to the layered fabrics on the table and heighten the color.

Starting in the 1920s, Duncan Phillips, founder of The Phillips Collection, helped to introduce Braque’s paintings to a wider American audience through acquisitions and installations. In the 1930s, Braque’s art continually appeared in major international exhibitions and publications as his European and American supporters encouraged interest in his work. Although Braque did not exhibit frequently during World War II, in 1943 he was honored with a special room of recent works at the Salon d’Automne in Paris. In their focused subject of modest objects grouped on trays and washstands, some saw disengagement from current events; for others, the visual realm of the still lifes represented a space for creative freedom during tragic times, an escape into intimate and imaginary spaces.

The exhibition is co-organized by The Phillips Collection and the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, part of the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis.

Exhibition Catalogue

The fully illustrated catalogue includes essays by exhibition co-curators Renée Maurer of The Phillips Collection and Karen K. Butler of the Kemper Art Museum and others. The catalogue also includes an in-depth study of Braque’s materials and process by Patricia Favero, Phillips associate conservator, Erin Mysek, Andrew W. Mellon postdoctoral fellow in conservation science at Harvard Art Museums, and Narayan Khandekar, senior conservation scientist at Harvard’s Straus Center of Conservation. Available in the Museum Shop

Exhibition Support

The exhibition is supported by the Share Fund and an award from the National Endowment for the Arts

The exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

Artist Profile

Georges Braque (1882–1963) was a profoundly influential French modern painter who, together with Pablo Picasso, developed the radical pictorial language of cubism, shaping the course of 20th-century painting. Born in Argenteuil, France, Braque came from a family of decorative house painters, a background that taught him to re-create complex surfaces and visual effects. After completing a two-year apprenticeship in the family business in Le Havre and Paris, he entered Académie Humbert at age 20 to study fine art.

Passing through impressionist and then fauvist styles, Braque became increasingly concerned with volume and structure, inspired by the works of Paul Cézanne. It was at this point that he and his friend Picasso engaged in a rigorous analysis of form and developed cubism. In 1912, Braque created the first of his paper collages, initiating what would become a lifelong concern with the tactile depiction of space.

During Braque’s military service in World War I, he sustained a head injury and did not resume painting until 1917, when he began classicizing and naturalizing the cubist vocabulary. Braque’s work in the 1920s included small still lifes and large, complex canvases with rich, velvety textures; these gave way in the 1930s to paintings with vibrant colors and bold patterns. By the mid-1930s, Braque was an internationally recognized still life painter and regularly included in exhibitions and publications. He was in Varengeville in Normandy when the Germans invaded France in 1940. During the German occupation, Braque lived and worked in Paris, returning to Varengeville after the liberation of Paris in 1944.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Braque took on two ambitious series, Billiard Tables and Studios,and his work continued to appear in numerous museum exhibitions. In 1948 he received first prize at the Venice Biennale, in 1951 he was awarded the Légion d’Honneur, and in 1961 he was the first living artist given an exhibition at the Louvre. When Braque died at age 81 on August 31, 1963, funeral services were held in front of the Louvre.

Phillips Connections

Duncan Phillips, founder of The Phillips Collection, played a vital role in introducing Georges Braque to American audiences. In 1927, he became the first U.S. museum director to purchase a painting by Georges Braque for a public collection—Plums, Pears, Nuts, and Knife (1926). Phillips, who was already interested in French modern art, saw in the artist a kindred spirit, an independent mind with ties to tradition. During the 1920s, Phillips purchased four more Braque paintings similar in palette and composition, including Lemons, Peaches, and Compotier (1927).

By the 1930s, Phillips’s tastes as a collector had evolved. He was fascinated by a more experimental painting by Braque, The Round Table (1929), which he purchased in 1934. At the time, The Round Table was the largest, most colorful abstract painting in the museum’s collection, a symbol of Phillips’s embrace of innovative work by living artists. Phillips considered it one of Braque’s “greatest and most exciting [canvases]. … It is functional and majestic in its forms and in its chromatic range it is exultant.” After its acquisition, Phillips began installing paintings by Braque in groups in the museum’s galleries.

In fall 1939, the Arts Club of Chicago organized Braque’s first U.S. retrospective, featuring nearly 70 works from many sources, including the Phillips. Duncan Phillips then hosted an adapted version of the exhibition at The Phillips Collection, providing Braque’s first U.S. museum retrospective. In the exhibition brochure, Phillips suggested his own preference for Braque’s work over Picasso’s: “Time may rank the mellowed craftsmanship and enchanting artistries of the reserved Frenchman higher than the restless virtuosities and eccentric innovations of the spectacular Spaniard.”

Duncan Phillips was moved by the wartime works Braque had produced in Paris, which often showed scenes of daily life, with still life elements displayed on kitchen tables, trays, or washstands. In 1948, he purchased The Washstand (1944)and exhibited it almost immediately. A year later, Phillips lent other works by Braque to a large retrospective in Cleveland and New York, but he kept this new acquisition on view in his museum.

Duncan Phillips ultimately acquired 11 of Braque’s oil paintings. Phillips also left his museum another remarkable connection with the artist. In 1959, he received Braque’s permission to have a bas-relief designed after one of the artist’s prints to be used as a decorative entrance element for the museum. This symbol of a bird in flight remains a significant icon of The Phillips Collection’s identity.