Degas’s Dancers at the Barre

Point and Counterpoint

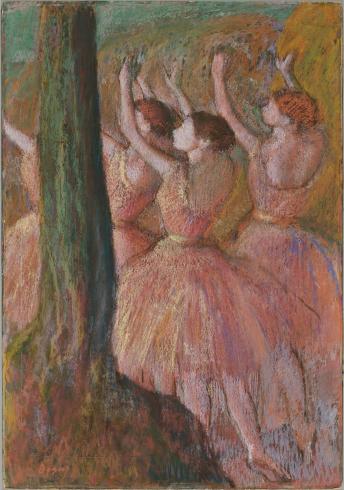

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (1834–1917) was a passionate devotee of ballet—he knew the dancers, the music, the choreography. He also knew the work involved in the life of the dancer, the endless repetition of steps to achieve grace, agility, and expression. He pursued the subject for over 40 years through oils, pastels, drawings, prints, and sculpture, creating over 1,500 works devoted to the anatomy, posture, and movement of dancers. Degas’s Dancers at the Barre: Point and Counterpoint is the first exhibition of Degas’s dancers in Washington, D.C., in 25 years.

The impressionist master’s relentless experiments with movement and dance culminated in Dancers at the Barre (early 1880s–c. 1900), one of the greatest works in The Phillips Collection. The exhibition brings together about 30 related paintings, works on paper, and bronzes, created between 1870 and 1900, from some of the world’s greatest collections, including the NY Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen; Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo; the British Museum, London; the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; and the Corcoran Gallery of Art and Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, D.C. The exhibition also features work by Degas in the Phillips’s permanent collection.

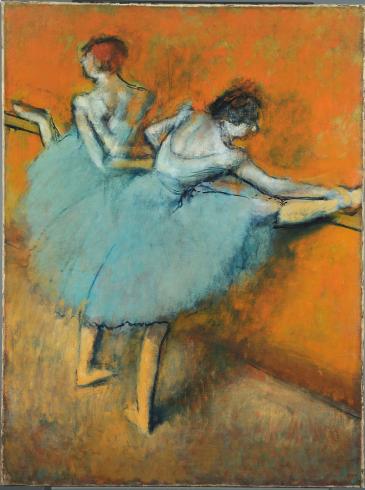

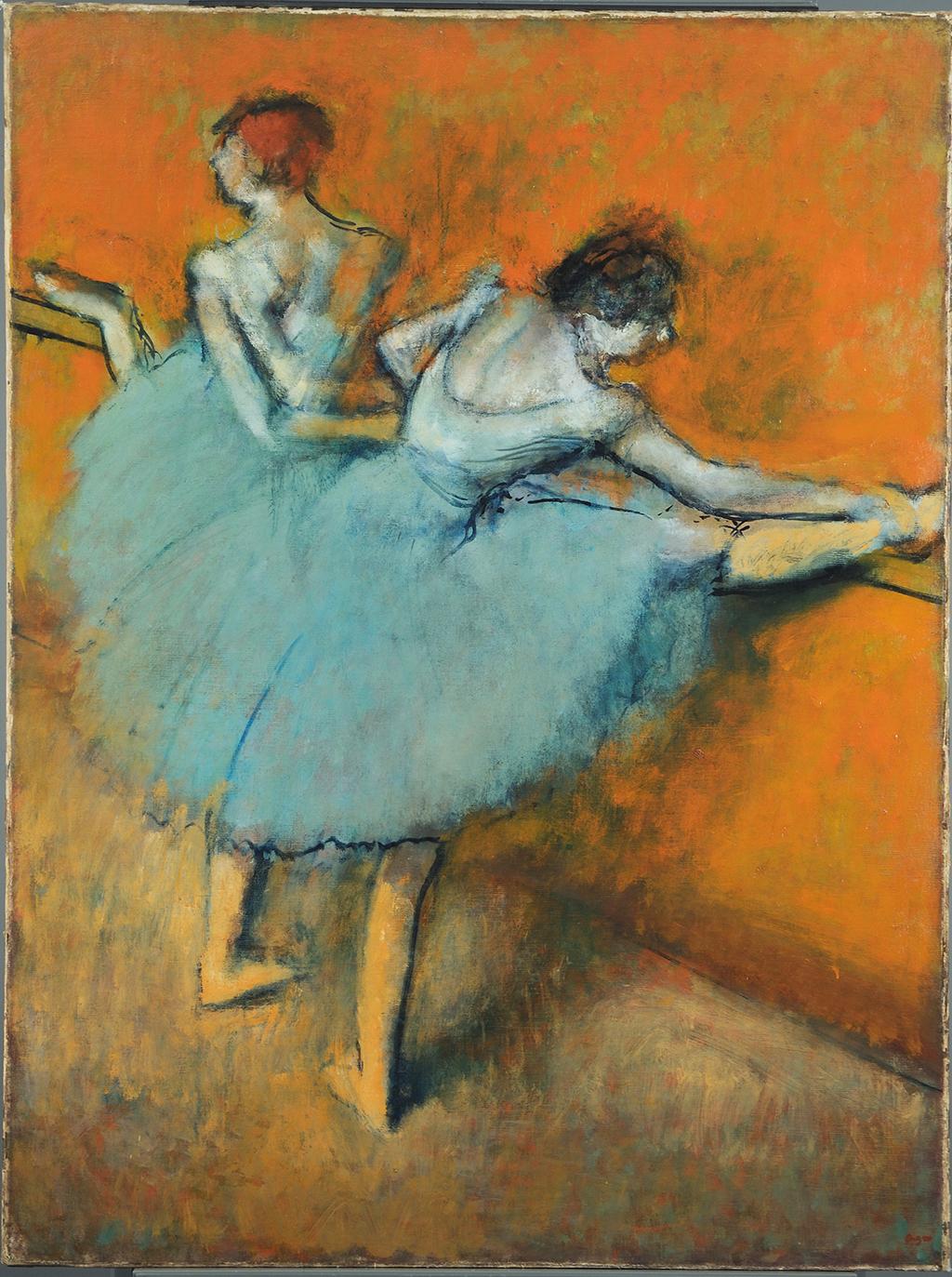

Early in 2007, Head of Conservation Elizabeth Steele set out to rescue Dancers at the Barre. The painting’s aging varnish, flaking paint, and years of airborne grime endangered its structural stability and diminished its aesthetic appearance. Steele restored a lustrous palette of bright blue, white, and black against a flaming orange background, and located an inscription on the canvas indicating it was begun around 1884. She also uncovered evidence that Degas cut the canvas down after the painting was underway, repositioned the dancers’ arms and legs at several times, and daubed paint on a dancer’s neck with his thumb. These discoveries indicate that he began the painting before 1884 but returned to it several times over the next two decades, intensifying its color palette and repositioning and blurring the contours of the figures.

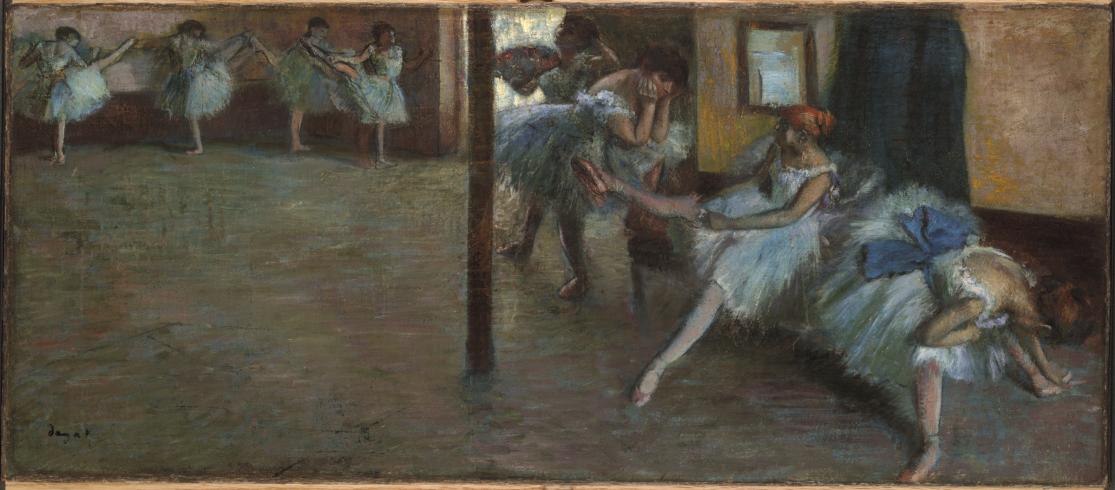

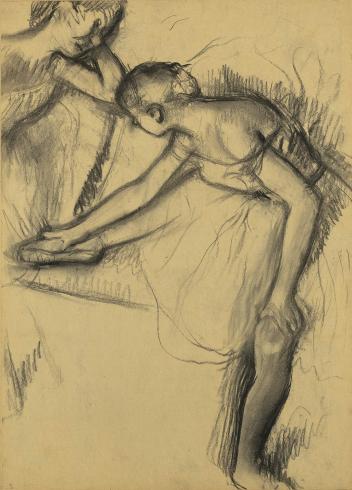

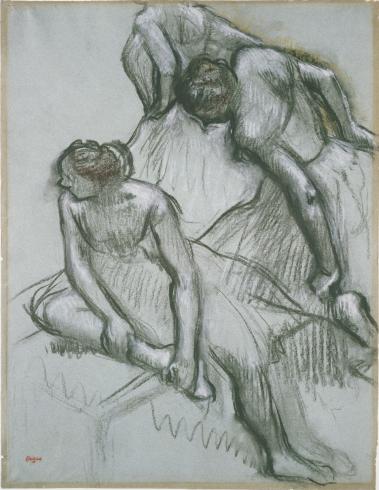

Degas’s process mirrored the rote and repetition, point and counterpoint of ballet—he repeated himself obsessively, tracing and refining compositions over decades, and reproducing the same subjects from multiple perspectives in a range of media. He often produced studies for individual dancers or small groups then combined their figures in new compositions. Occasionally, he stripped away costume to deepen his understanding of anatomy and posture. Dancers at the Barre is reunited with full-scale pastel and charcoal sketches of its dancers shown individually and together, nude and clothed, for the first time since they were in the artist’s possession.

For museum founder Duncan Phillips, Dancers at the Barre was “a masterpiece … in its daring record of instantaneous change at a split second of observation,” in which Degas “miraculously transformed the incident of swiftly seen shapes in time into a thrilling vision of dynamic forms in space.”

The exhibition is organized by The Phillips Collection.

Artist Profile

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas was a prolific, influential French impressionist who brought together the academic tradition of draftsmanship with close observation of modern life in Paris, the city in which he lived his entire life. His many subjects included the offstage world of the ballet, a subject to which he returned in more than 1500 works over four decades.

The son of a banker, Degas was born in Paris on July 19, 1834, and, as a young man, briefly studied law. In 1855, he entered the Academie des Beaux-Arts, where he studied under Louis Lamothe, a student of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and became accomplished in drawing. Between 1856 and 1860, Degas visited Naples, Rome, and Florence to view and copy the works of the Italian Old Masters. On a trip to Rome in 1858, he became friends with French painter Gustave Moreau.

During the early 1860s, Degas painted large compositions and portraits. He began showing his work at the Salon in 1865. Degas was active in organizing the first impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1874 and participated in most of the subsequent impressionist shows.

In about 1892, in his late 50s, Degas started working mainly in pastels. At this time he started to experience problems with his eyesight and began working with low light levels in his studio. Later in life, he concentrated on collecting paintings, favoring the works of Ingres and Eugène Delacroix. Edgar Degas died at age 83 in Paris on September 27, 1917.

Exhibition Support

Proudly sponsored by Lockheed Martin

Made possible by Pernod Ricard

The exhibition is supported by a generous gift from Perry and Euretta Rathbone.

Choreographer’s Notes

The following is excerpted from an exclusive interview by Wall Street Journal dance critic Robert Greskovic with internationally recognized choreographer Christopher Wheeldon from July 2011. The full interview appears in the Degas’s Dancers at the Barre: Point and Counterpoint exhibition catalogue, available mid-November in the museum shop.

Excerpts from Swan Lake choreographed by Wheeldon for the Pennsylvania Ballet in 2004 are on view in the exhibition.

RG: When you staged Swan Lake in 2004, you chose a Degas era. Can you tell us what interested you in Degas?

CW: Two years previously to Swan Lake, I’d been to Degas and the Dance at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and had been intrigued by many of the backstage paintings and the perspective from the wings—looking through the dancers, watching dancers performing on stage, there are these black, tall, top-hatted figures. … I think what struck me most of all was how accurate all these paintings are in their depiction of the rehearsal process and how things haven’t really changed. The outfits have changed. … The way that the light comes in through the windows of the studio, that’s something that I felt was very accurate, how I feel when I’m in the room and how the light affects the way that I work, and also just the vividness of the colors in the paintings, the theatricality of them just pulled me in.

RG: While you were working in Philadelphia, did you find that the dancers, for whom you were making the ballet, had a familiarity [with Degas]?

CW: Basically what I did was I took color Xeroxes of every Degas painting that I could find and pasted them up all over the studio, and I encouraged [my dancers] as much as possible to look at the way the dancers are posed, the very naturalistic way. They’re dancers, that’s what dancers do, you see them sitting around the room in the same poses that you see in these paintings. You put a ballerina today that’s wearing a dirty pink leotard in an old practice skirt to rehearse Giselle and she looks exactly like one of the figures in a Degas painting, so even that hasn’t changed that much.

RG: What immediately strikes you about [the paintingDancers at the Barre]?

CW: I think what’s interesting about this is the positioning of the dancers, the figure in the background, how overly forced her front leg is on the barre. It’s an unnatural amount of turnout that she has and that’s exactly what dancers do when they warm up, you know. When dancers warm up, they go to the barre, and they force their bodies beyond the positions that they’re expected to be in as a dancer in order to push the muscles to a point where they get warm.

Curator’s Notes

To place its title painting in context, says Phillips Chief Curator Eliza Rathbone, Degas’s Dancers at the Barre: Point and Counterpoint brings together approximately 30 stunning works by Degas—including paintings, bronzes, drawings, and prints—from major collections around the world and the museum’s permanent collection. “Dancers at the Barre is a great, late Degas masterpiece, so you need to understand Degas’s whole evolution to see where it comes from,” she says. “Certainly, you need to follow his interest in dance and ballet over a number of decades from the 1870s past the year 1900.”

One of the best known holdings at the Phillips, Dancers at the Barre is also a timely exhibition subject because of the discoveries that were made during its recent conservation, revealing how Degas repeatedly changed the dancers’ positions and intensified the color palette. Technical images from this scientific study are included in the exhibition, shedding light on the artist’s process of frequent revision—just as the other works in the exhibition show Degas revisiting the subject in different media. The exhibition’s subtitle, Point and Counterpoint, “evokes Degas’s own repetitive work as he continually revisits, revises, and works through his visual ideas,” says Rathbone. “The exhibition brings out the parallels between Degas’s work and dance itself, both of which require incredible discipline and dedication—there’s nothing halfway about either one. It has to be total love to achieve greatness.”

Above all, she says, “these are ravishingly beautiful works. I hope that the visitor is deeply moved, inspired, and engaged by the passion with which Degas pursued his work and the greatness of his achievement, and comes away marveling at his invention. It is really an extraordinary life, and even people who have spent their own lives studying Degas never stop making new discoveries; it is that rich.”